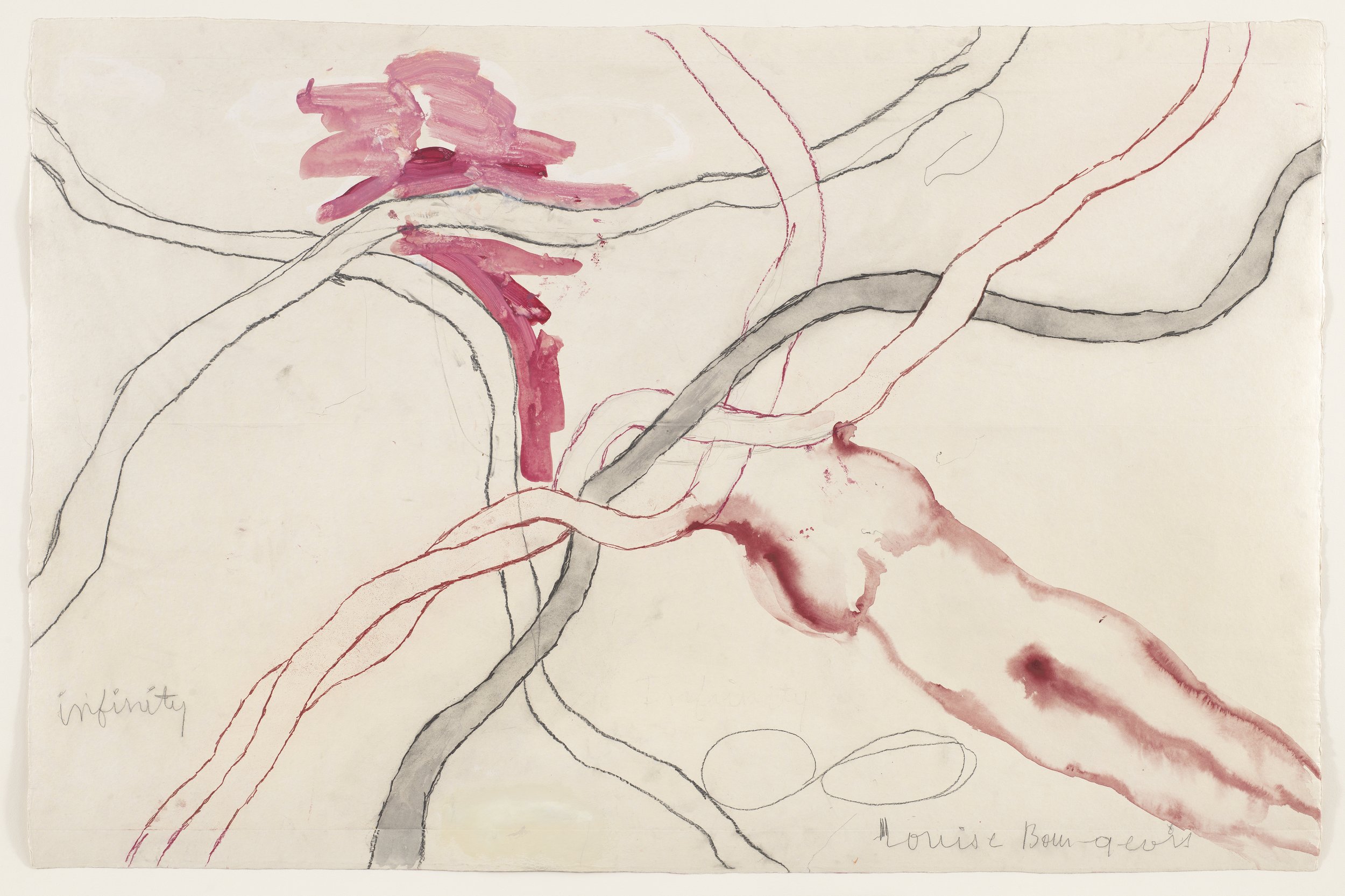

Louise Bourgeois (1911–2010). No. 5 of 14 from the installation set À l’Infini. 2008. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. © 2017 The Easton Foundation/Licensed by VAGA, NY

The Squid and the Bees

by Emily H. Brout

Tiger heads rest on the bottom of each leg of my mother’s wooden vanity table, their fangs piercing the carpet. This is fitting because my mother tortures me in front of her vanity each morning. She always forgets to do the trick—squeezing the hairs near the top as she brushes so my scalp can’t feel the tug. I’ve had this argument with her so many times. She doesn’t care that it is my hair. My head jilts with each stroke. I am fine with being ugly. I’ve accepted my saggy nose. My nostrils look like pinpricks a bug couldn’t crawl through.

“Honey, if your hair is all frizzed and dirty, people will think poorly of you.”

My mother did not care about my appearance before I was diagnosed with dyslexia and a cocktail of other learning disabilities. She says my appearance is important because I’m becoming a young lady, but I know she agrees I’m stupid and is looking for a way to give me an advantage.

“It’s sweet you want to emulate your father, Agatha, but his shirts are way too long to wear in public. People can’t tell you’re wearing shorts underneath. Pick out something nice from my side, won’t you?”

My mother’s walk-in closet is to the left, and my dad’s is to the right. I go into my mom’s closet. Her dresses are hanging inside plastic covers, her shirts are stacked in white cubbyholes, and she has three scales balanced on the shelves. Her clothes are small. She is petite and only eats when nothing is wrong, but something is always wrong. I just think she likes to look tiny. It’s why she buys all these big bulky bags. Deep down she wants to be the child.

The closet smells like vanilla. I hear bees. My mother says the buzzing is in my head. When I mentioned it to dinner guests last week she kicked me under the table. She says people will think poorly of us if they think we are living in a house with bees. She says people will think I’m crazy for hearing bees no one else hears.

She wants me to pick out something nice. I’m taller and wider than other girls my age, so her clothes fit me. I choose a pink shirt with a poodle on it and a long corduroy skirt. I take one of her purses—one that is large enough to fit a Yorkie inside—off the shelf and wait until I hear my mother go into the bathroom.

My dad’s closet smells like cigars. When I was younger and he was around more he’d take me on the porch and fake smoke with me. I would practice being like him, being boss.

I grab a pair of his basketball shorts from the cubby; the shorts stay up because you can make them as tight as you want by pulling the strings. I take a black collared shirt and shove everything into my mom’s purse.

My mom is hanging chandelier earrings in the holes of her lobes. Her reflection in the bathroom mirror smiles at me.

“A purse too! You look fantastic.”

I feel like a dog wearing human skin.

On my walk to school I change behind a bush. I shove my mother’s shirt and skirt back into her purse and shove the purse under the bush. I shove some leaves on top so no one will see it. I can’t walk into school with my mother’s purse. Everyone will smell how wrong it is.

The school’s checkered floor is covered in hair because all the girls compulsively brush, and gum wrappers because everyone has anxiety issues. I can hear the worms crawling underneath the hallway. It is their job to mix the dirt. I want to rip up the tile and let the worms breathe, even if the tile is protecting them from being trampled beneath middle school sneakers. I want to give the worms an aboveground burial.

I am standing outside the girls’ bathroom that smells like the lavender air fresheners janitors have mounted to the walls. The boys’ bathroom smells like the urinals mounted to those walls. I pause to plug my nostrils between my forefinger and thumb.

“Shit,” a voice says from the girls’ bathroom.

I forget the worms and the pee smell and press my back flat against the door to swing it open.

“Hello?”

“Agatha, is that you?” Debbie asks.

“How did you know?”

“Your feet. My brother’s pigeon footed too,” she says.

I’m not pigeon footed. I get pain in the bottom of my feet, so sometimes I shift my weight to the outside. It never occurred to me that anyone would notice. I didn’t think Debbie knew anything about me. Does she think my feet are unattractive? Is it good or bad to remind someone of their brother?

“Okay, so listen, I know this will be one of those things people immediately feel bad about because they think the person who’s confiding in them feels embarrassed, so before I tell you what’s going on, I want you to know I’m not embarrassed at all.”

“Okay?”

“I have a situation. I’m wearing white shorts, and there’s a huge blood stain in the center of them, and I don’t know what to do. Like it’s The Shining bad.”

“Can I see what we are dealing with?”

The toilet seat drops. I can see her bare feet. She takes off her shoes when she is on the toilet? That’s adorable. A pair of white booty shorts skates across the bathroom floor like a hockey puck on ice. Along the center seam is this bull’s-eye of a stain. Debbie must have a symmetrical labium because that’s an absurdly centered stain. It’s shaped like a butterfly. I hold it up with two fingers.

“Kind of looks intentional.”

“I do not think people are going to think that when they see it.”

Debbie opens the stall door. Her bottom half is wrapped in toilet paper. She takes tiny steps to stay mummified. Her shoes are on top of the toilet. She tightens her lips, a dimple forming on the left side of her cheek, eyes on the door.

I forget I’m holding her bloody shorts. I think about how she cups her hands in her lap in science class. I wish I could give her my mom’s skirt even if it is too long. The woman from The Shining wore a long skirt and it was covered in her husband’s blood or maybe it was the other way around. My mom always told me not to freak out if I saw blood in my underwear. She told me if I ever found blood to tell her so she could start the abortion fund. After she told me that I compulsively checked. I have not stopped.

“Do you have a pen?”

Debbie leans down carefully and fishes in her purse. She throws me a blue pen. I bite the head of it, take out the skinny plastic holding the ink, and bite down again. Ink explodes in my mouth but also on the shorts. I splatter what’s left in the tube, the ink and blood mixing.

“Sorry I’m ruining your shorts,” I say.

“I’m not going to wear those ever again,” she says.

I take off my shorts and throw them to her. Debbie forgets she is a mummy, takes a thoughtless step, and some of the toilet paper rips. She crosses her legs and twists around. She’s not wearing underwear. She must have thrown them out.

I turn around too and put on her shorts. They’re tight over my hips. I wish my hips were wooden so I could carve them off with a saw to fit Debbie’s shape.

I turn back around and Debbie is wearing my father’s shorts.

“You aren’t grossed out? My blood is touching you.”

I shake my head as the bell buzzes, signaling the start of classes.

“You’re a lifesaver,” she says. She plants a kiss on my forehead before she leaves the bathroom.

Louise Bourgeois (1911–2010). Triptych for the Red Room. 1994. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of the artist. © 2017 The Easton Foundation/Licensed by VAGA, NY

The guys in Life Science class call me squid because I am so inky. A girl asks, “Is that blood?”

I look at Debbie who is not looking at me. She is talking to Christian, the guy who started calling me squid. I clench my jaw until my teeth hurt. Debbie is close enough for me to touch her. I touch Debbie’s arm because I need her to say something nice about me. Her arm is smooth, not like mine. The hairs on my arms are elaborate, like crop circles, but I am the only one that likes the tufts branching out in different directions.

“Dykes,” Christian says, and Debbie winces, pulling her arm away.

Maybe what happened in the bathroom was not as meaningful as I thought. Could I have hurt her feelings without realizing? Is there something bad inside of me? Why do I feel heavy chested? I take a deep mouthed breath. I know it makes me look funny, but if I suck in all the air, I can calm down.

“What about the bathroom?” I ask the back of Debbie’s head.

“What you do in the bathroom is your business,” she says. She doesn’t turn around.

I forget to stop by the bush after school, and when I get to my house, my mother is barefoot on our lawn. She’s talking to a guy whose shirt reads BEST CANFALL. My mom doesn’t notice me sneaking by in my father’s black collared shirt and Debbie’s ruined shorts.

“Honestly I don’t know how you didn’t hear them before,” the man is saying. “You’ve got two hives in that wall. We’re going to have to demolish your closet.”

I climb the tree closest to the fence in the backyard. Two men wearing white suits are razoring through my mom’s closet. One of them is holding a metallic boxy vacuum with tubing stretching around the side of the house. The bees are silent and still behind rosy cotton candy insulation. One man makes more cuts into the wall, pulling out the insulation until I can see the wooden beam holding the room together. There is a brown cluster of hive in front of the beams. The second guy lights the base of a large horn and smoke pours out of the nozzle. The cluster of brown scatters, screaming, and the men begin to vacuum out the chunks piece by piece. When they have cleaned out most of the chunks, the two men clean each other. The smart bees are hovering around their suits, but they are vacuumed up too. The men shut the vacuum off, and it is silent. The waistband of Debbie’s shorts digs into my hips.

Published December 10th, 2017

Emily H. Brout lives and works in New York City like Cyndi Lauper or Giuliani. As a teenager, she was occasionally known as the vocalist in the rock band The Indecent. More recently, she has written many short stories one of which was recommended by Etgar Keret, translated into Hebrew, and published in Maaboret. She thinks this is pretty damn cool and may act as a psychic atonement for never having been Bat Mitzvahed. She has also written for Tom Tom Magazine, Feminine Collective, Flock, and the New York Observer.

French-American artist Louise Bourgeois (1911–2010) was best known for her large-scale sculpture and installation art, but she was also an accomplished painter and printmaker. “Louise Bourgeois: An Unfolding Portrait” is on view at the Museum of Modern Art in New York through January 28, 2018.